If you pause for a moment to reflect on your own journey, have you ever wondered whether life is meant to unfold in a specific order—one that respects both your personal growth and your place in the world? This is precisely the vision laid out in the ancient Vedic ashrama system, a framework that divides a human life into four dynamic stages. Each phase, from the first step as a student to the last as a renunciant, is designed not only for personal fulfillment but also for the well-being of society.

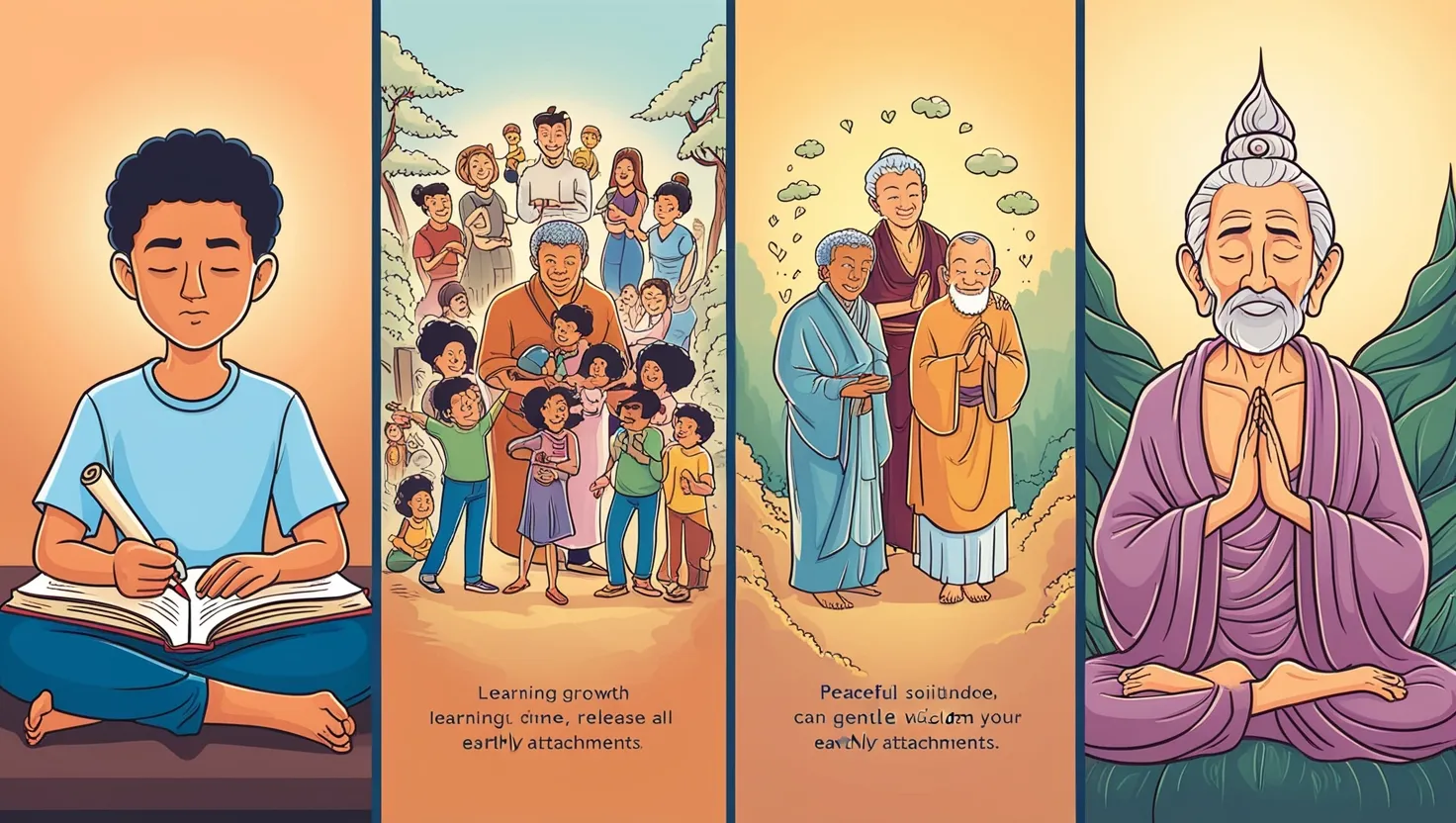

Let’s start at the beginning, with brahmacharya, the stage of disciplined learning. I see this phase as far more than merely accumulating information from books or absorbing the rules set out by parents or teachers. It’s an all-encompassing training ground where you shape your mind, body, and spirit for everything that lies ahead. The discipline practiced here is not meant to stifle but to liberate. Imagine a period where the art of asking questions—big ones, small ones, inconvenient ones—is both encouraged and expected. “Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire,” said W.B. Yeats. While the Vedic student was asked to memorize sacred verses and learn practical skills, the unspoken goal was to build a character rooted in self-restraint, curiosity, and compassion. Without this foundation, none of the later stages would have the strength they require.

What’s fascinating is that, unlike modern education systems which tend to confine learning to youth, this phase was deliberate preparation for a lifetime of inquiry. The insistence on celibacy and simplicity was not just moralistic; it was practical. The ability to direct desire into the search for wisdom is a skill that endures far beyond adolescence. How would your life look different if the primary goal of your early years was to master yourself, rather than just prepare for a job?

As one transitions to grihastha, the householder phase, the energy shifts from containment to engagement. This is the moment where the lessons of discipline are tested in the messy world of relationships and responsibilities. Far from being a mundane stage of routine, the householder’s task is both audacious and complex: to contribute to society, raise ethical children, and fulfill obligations to family, work, and community. The grihastha stage doesn’t see material pursuits as distractions but as opportunities for growth, provided they’re guided by a sense of dharma, or right action.

It might sound surprising, but this stage is often considered the linchpin of the entire ashrama system. Every other stage relies on the householder’s capacity to produce, nurture, and support. The generosity and stability of the grihastha fuel students, offer guidance to elders, and allow renunciants to thrive outside economic concerns. Why do we so often see the middle years as a time of stagnation, when, in the Vedic view, they represent the creative core of life?

“Act, but act without attachment,” insisted Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita. Worldly success is not shunned but rather put in perspective. The emphasis here is on moderation and service, showing that spiritual growth is not an escape from the world but a way of living fully within it. The constant balancing of pleasure, duty, wealth, and liberation keeps life from collapsing into mere routine. I find it radical that the Vedas ask us not to reject desire, but to steer it with wisdom.

As children mature and the demands of daily activity decrease, one naturally transitions into vanaprastha, often called the retreat or forest-dweller phase. Here, the energy subtly shifts again—from creation and support to withdrawal and reflection. The person is neither fully immersed in the world nor completely renounced. Instead, this period exists in the space between.

What intrigues me is that vanaprastha is not sudden isolation or abandonment of obligations but a gradual turning inward. Advice and mentorship replace management and control. Older adults are encouraged to serve as guides and counselors. Life becomes lighter, materially simpler, and spiritually richer. “In the depth of winter, I finally learned that within me there lay an invincible summer,” wrote Albert Camus, capturing the spirit of this phase. The deliberate creation of solitude is not an escape; it’s an act of integration, where one finally has the time to make sense of the years lived.

Have you ever noticed how modern life rarely grants permission—even tacitly—for this kind of pivot? The expectation is often that one continues producing, consuming, and striving in the same mode until energy runs out. The ashrama system, in contrast, celebrates shifting priorities, seeing reflection and winding down as acts of courage equal to the exertion of youth.

All journeys culminate, sooner or later, in sannyasa, the ultimate letting go. Contrary to popular images of hermits and ascetics, the true sannyasin is not defined by what he or she gives up, but by the freedom gained. This stage is marked by complete renunciation of personal ambition, possessions, binding social ties, and even the structure of the ashrama system itself. The sannyasin is free to focus entirely on the pursuit of self-knowledge, wisdom, and—ideally—helping others find their own path to release.

What stands out here is the clarity with which the Vedic tradition identifies freedom, not as a right, but as something one gradually earns through self-mastery and fulfillment of prior stages. The renunciant no longer acts for personal benefit. Their wisdom and presence can become a quiet force for healing, inspiration, and change. “Freedom is not worth having if it does not include the freedom to make mistakes,” said Mahatma Gandhi. Yet the mistakes of the past are not burdens to the sannyasin—they are simply left behind.

This progression from student to sage preserves a delicate balance between individuality and community. While each person’s journey looks different in detail, the ashrama framework offers a shared structure for living well and dying wisely. It acknowledges the drives to acquire, possess, serve, and relinquish, integrating them into an arc that makes each stage meaningful. Even if you resist the idea of living according to ancient scripts, it’s hard not to appreciate the psychological sophistication here. Every urge is permitted, but each is contextualized and eventually transcended.

Modern psychology has only recently begun to recognize something the Vedas coded long ago: a meaningful life is not defined by unvarying striving or static contentment, but by transformation and gradual refinement of purpose. Erik Erikson’s ideas about identity, generativity, and integrity echo these ancient insights, but the ashrama model weaves them into a social and spiritual narrative.

Let’s consider the practical side. How might life look if we used these stages, not as strict laws, but as inspiration for intentional living now? Imagine dedicating your youth to inner and outer learning, not rushing the process. Envision a period when your main focus becomes building, nurturing, and contributing, embracing work not just for its own sake but as a sacred act. Then, allow yourself space and time to gradually shift focus to guidance and deeper knowing, savoring solitude without apology. And finally, prepare to let go completely and devote your life, even quietly, to wisdom alone.

Here’s a question to sit with: If you knew that the different chapters of your life were meant for entirely different pursuits, how might that change the way you make decisions today?

It’s worth noting that very few people in any era have followed these stages in their pure form. Even the Vedas understood that circumstances, personality, and societal changes alter life’s course. The exact boundaries between phases are blurred, the transitions messy. Yet, the real value may lie in the principles: discipline before indulgence, service before withdrawal, detachment before renunciation.

As you contemplate your own journey, consider whether today’s world, fixated on ceaseless productivity, could benefit from designating clear phases for growth, contribution, reflection, and release. Are you holding on to roles or ambitions that once gave meaning but now simply exhaust? What would it be like to let yourself live in tune with your stage, not fighting for perpetual youth or clinging to obsolete dreams?

Through this lens, aging changes from decay into progression, the passage of time into a story of continuous renewal. Each stage is both an end and a rehearsal for the next—a spiral rather than a straight line.

“If your compassion does not include yourself, it is incomplete,” wrote Jack Kornfield. The ashrama system reminds us that compassion involves giving ourselves permission to grow, change, and even retreat. We serve best, teach best, and experience life most deeply when we respect the particular season we are in.

In the final reckoning, the Vedic vision is not rigid. It’s a living philosophy, urging us toward a conscious unfolding of our own potentials. The ashrama system doesn’t dictate what we must do at every age, but it does hold up a mirror: Are we evolving, settling, or resisting the journey? If you ask yourself these questions with honesty, you have already begun to live its wisdom.