Have you ever wondered why so many ancient stories focus on floods, and why the Matsya Purana’s version stands out with layers that extend well beyond saving humanity? When I sit with the story of Matsya, the first avatar of Vishnu, I find fresh meaning emerging every time—a set of insights that challenge assumptions, poke at the edges of what’s obvious, and ask us to think differently about beginnings, endings, and human responsibility.

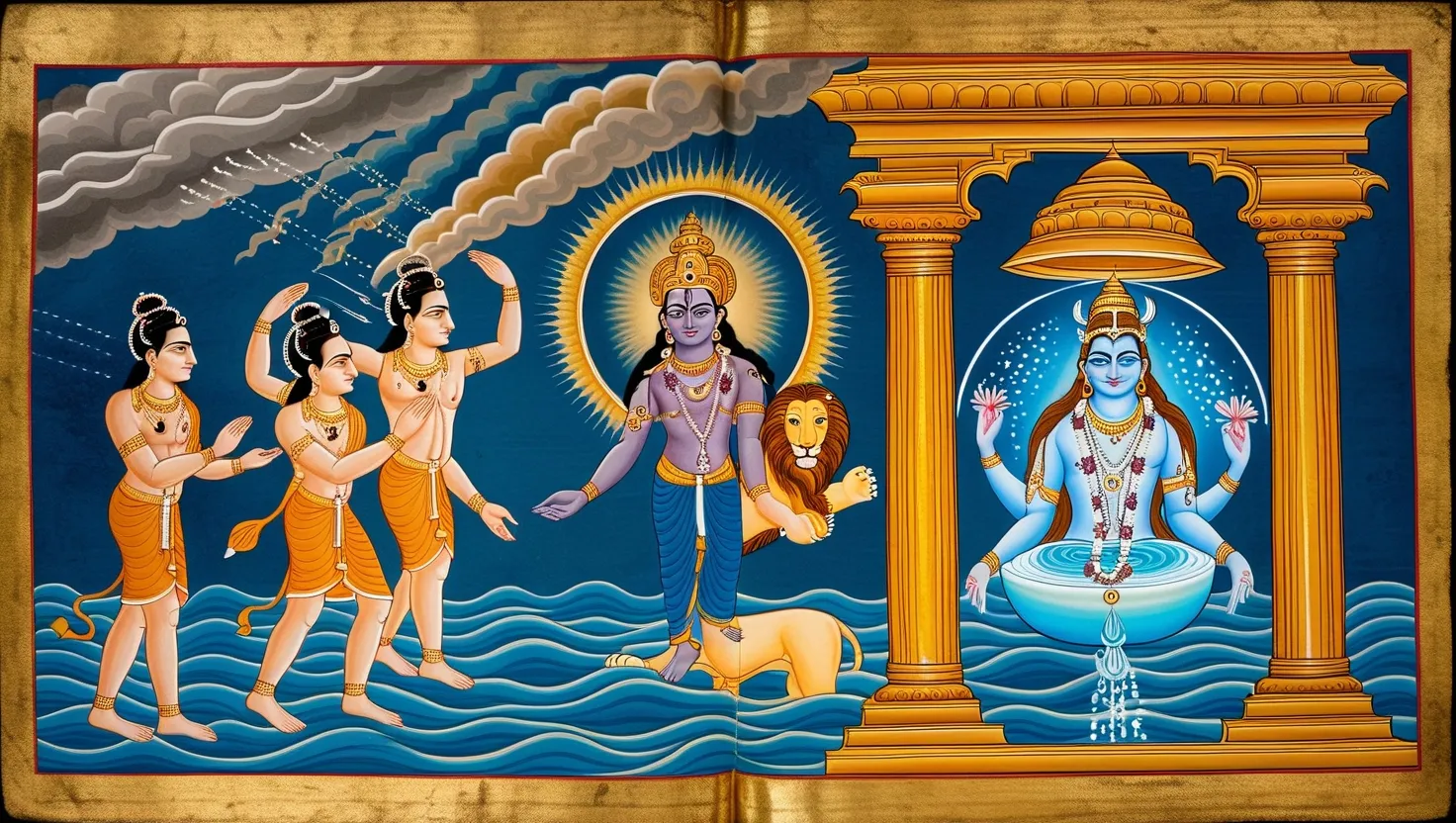

Let me take you into the heart of this story, rather than merely its surface facts. The image that lingers is not just a fish growing impossibly large or a divine boat roped to its horn, but a careful, deliberate process—a drama of trust, attention, and cosmic cycles. It’s not only about destruction and rescue. It’s about why such an epic reset is needed at all, what gets preserved, and who is called upon to do the hard, often thankless work of renewal.

“From the Mahabharata: ‘Time, verily, matured, moves forward with all beings; so all things at one time become manifested.’”

Why a flood? Before the deluge even hints at swallowing the world, the texts insist the problem isn’t random wrath. The ancient world of Manu had frayed its moral fabric. Decay had crept into every corner; balance had been lost. The flood is both consequence and medicine—an act that clears not with blind violence, but with intent to give the world another chance. The idea here is radically cyclical. Time loops in immense spirals, with creation, preservation, and dissolution each having their natural place. It’s less about punishment and more about what’s necessary for anything new to grow. Isn’t there something liberating in the idea that even worlds get a restart, not just people?

The hero of this story, King Manu, is no bystander. If you examine the details, you’ll notice he is not saved against his will or swept up by accident. Instead, he’s attentive—he notices the tiny, trembling fish in his palms rather than carelessly tossing it back into the river. He listens deeply, heeds instructions, and does the work (and what work it is!) of gathering the seeds, the sages, the texts, the living memory of a civilization. Faith is not idle here; it’s practical, muscular, full of action—an insight that shakes us free from seeing preservation as a passive virtue.

“The intuitive mind is a sacred gift and the rational mind is a faithful servant.” – Albert Einstein

Why is the growing fish important? It represents more than Vishnu’s concealed form. Early trouble often looks trivial. The fish, at first, is almost dismissible—just another little voice needing help. If Manu had ignored it, disaster would simply have arrived unannounced. The lesson is clear, and surprisingly contemporary: ignore small warnings at your own peril. This theme, subtle as it is, threads through the entire narrative. How many times do we overlook signals, brushing aside minor imbalances until they become full-blown crises?

I often think about the boat as one of the most extraordinary symbols in this story. It’s more than a floating refuge; it’s a carrier of life’s continuity and memory. It holds not just biological seeds, but the very Vedas, the texts that encode wisdom and identity. In this sense, I see the boat as a time capsule, but also as a society’s intentional act of curation—saving not only bodies, but stories and knowledge. The narrative takes pains to show that destruction is not total; salvage is always selective, and what’s saved shapes what comes next.

Here’s a question: If you had to choose what knowledge and memories to carry forward, what would you save? In the Matsya Purana, it’s not only chosen by the gods, but entrusted to a mortal acting on faith and discernment. The preservation effort becomes a partnership—divine and human, instructor and worker.

“History is not a burden on the memory but an illumination of the soul.” – Lord Acton

Another striking twist comes from what happens after the flood. The boat doesn’t just drift aimlessly. Guided by the fish, it moors upon the mountains, a symbolic altitude—a literal and figurative higher ground. This isn’t about resetting back to ignorance; it’s about landing somewhere you can see farther, armed with learning and intent.

What about the more subtle, ecological layers? The Matsya Purana is rare in the way it sets the stage for mutual dependence. All creatures, great and small, are included in Manu’s mission, pointing to a holistic view of stewardship. Humanity’s task isn’t to dominate, but to act as caretakers for a living world whose health is bound to our own. The “seeds of all life” are not metaphor alone—they are the genome of continuity. This message rings truer than ever in an age where biodiversity and ecological balance face threats more insidious than flooding waters.

“Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better.” – Albert Einstein

A lesser-discussed element is the interplay of memory and instruction. The flood doesn’t simply wipe clean—what’s carried over, through the Vedas and the sages, is not only cultural but instructional. The Matsya avatar teaches Manu as they float, providing not just physical survival, but a framework for the next world. This illustrates a profound educational principle: true survival demands the transfer of wisdom, not just species or objects. How much of our own crisis management neglects this? Are we merely rebuilding, or are we finding ways to transmit wisdom so recall isn’t lost in the flood?

At every stage, the narrative returns to the idea of purposeful intervention. Vishnu’s descent isn’t arbitrary. Divine action matches the crisis—fish form for water; guidance for the worthy. This template, established by Matsya, echoes through the later avatars, each appearance tailored to context. The logic is pragmatic, not mystical—a deeply practical lesson, almost managerial, in responding to challenge with solutions suited to the situation.

What stands out to me is how the story—despite its mythic grandeur—grounds itself in the mundane. The work of saving the world is logistical: build the boat, gather the seeds, listen carefully, adapt quickly. Eternity is shaped by what we do with our hands today. I often ask myself, what “small fish” am I missing? What practical acts now will ripple into rescue or renewal later?

“Faith is taking the first step even when you don’t see the whole staircase.” – Martin Luther King Jr.

Comparing Matsya’s flood to other global flood myths, the Hindu version roots itself in restoration rather than mere judgment or destruction. Instead of only a warning or a harsh reset, Matsya brings the tools for humanity to begin again better prepared. Life’s fragility is matched by the resilience of those willing to heed early signs and act collectively.

Can you imagine being Manu—charged with starting civilization over, carrying the anxieties of loss and hope at the same time? The story puts extraordinary trust in ordinary attention. A fish saved in a moment of kindness becomes the oracle of fate. This inversion—the weak revealing itself as strong, the small as bearers of cosmic consequence—invites us to reconsider where we place our sense of importance.

“And in the end, it’s not the years in your life that count. It’s the life in your years.” – Abraham Lincoln

The Matsya Purana’s flood story reaches across centuries with a strangely modern voice. It tells us that catastrophe is never without cause, and that what is worth saving is more than just what can float but what can teach. It’s a mirror for our relationship with the world—a prompt to prepare, to listen, to act intentionally, and to trust that preservation is just as much about wisdom and memory as it is about numbers and species.

If we read the flood tale as only a myth, we lose its sharpest lessons. Read closely, it’s a survival manual written in the language of legend—an insistence on partnership, practical vigilance, and the recurring responsibility handed to those aware enough to notice the “fish” before the storm breaks. Isn’t that, in essence, the story of every human challenge—seen first as a trickle, then a flood, and finally as the origin of something entirely new?