Time in the Puranas never sits still. It is a force so immense yet so subtle that the best way I can describe it is to see it as a grand wheel, turning ceaselessly, sculpting existence and dissolving it again and again. What strikes me about the Puranic view is how it folds human anxieties and hopes into something far larger than our lifespans or even the age of the earth itself. Imagine standing on the shore and seeing not a single wave, but an endless tide—each crest a universe, each trough a cosmic slumber. This is how the Puranas talk about time.

Have you ever wondered why ancient tales seem so obsessed with cycles, with stories restarting, gods returning, and destruction always followed by a fresh creation? It’s because the Puranic worldview refuses to believe in finality. Time, here, is never a straight road. Instead, it’s an intricate pattern, an eternal pendulum, and each swing marks not just change but also the promise of return.

Let’s begin with the four Yugas, the epochs that shape human history. Each Yuga—Satya, Treta, Dvapara, and Kali—marks a step down a cosmic staircase. Satya starts as a golden era: virtue is abundant, human lifespan is long, and spiritual awareness is nearly universal. But as each Yuga flows into the next, virtue shrinks, confusion deepens, and our grasp of the sacred loosens. By the time we reach Kali Yuga, the age we inhabit now, things come apart. Corruption grows rampant, human lives shorten, and wisdom grows scarce. Is this a pessimistic view? Maybe. But the Puranas seem to tell us: Don’t panic. It’s part of a larger rhythm. Darkness, too, serves a purpose.

“What we call the beginning is often the end. And to make an end is to make a beginning. The end is where we start from.” — T.S. Eliot

Each complete sequence of four Yugas forms a Mahayuga, or Great Cycle. Picture a clock ticking not for hours but for millions of years—4.32 million, to be exact, for one entire Mahayuga. When the cycle ends, it starts anew, over and over. The point isn’t just to astound you with scale, but to remind you how small and precious a single human life is, and yet, how deeply it matters as a thread in this tapestry.

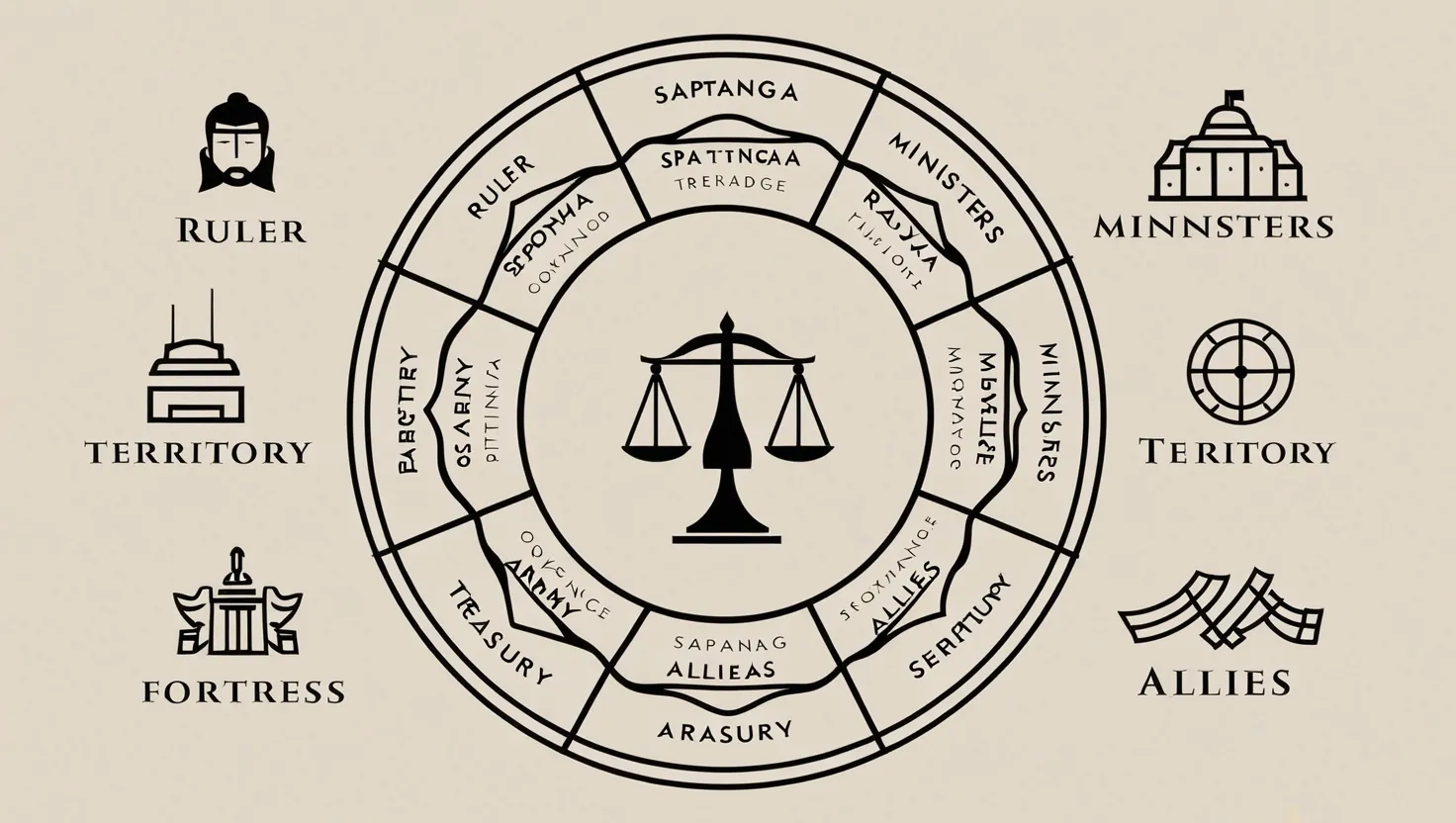

If the Mahayuga feels vast, consider the Manvantara. Each Manvantara spans 71 Mahayugas, overseen by a cosmic figure, Manu, who guides humanity for that age. There are fourteen Manus per Kalpa. This system is almost bureaucratic in its structure—a cosmic administration, with each Manu acting as a custodian, offering stability, guidance, and even regulation of cosmic law. It makes me wonder: in this cyclical cosmos, is leadership itself immortal? Or is it the values and principles that survive the churn?

“History does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” — Mark Twain

Then comes the Kalpa. A Kalpa is a day in the life of Brahma, the creator. To us, one Kalpa is 4.32 billion years—one thousand Mahayugas strung together. At the end of each Kalpa, the universe undergoes Pralaya, a cosmic dissolution. This isn’t a fiery apocalypse or an annihilation. Instead, think of it as rest: the universe withdraws, returning to its latent state. Nothing is truly destroyed; everything that was once manifest becomes potential again, resting, waiting to re-emerge.

Have you ever felt, in the quiet of night, that the world itself is holding its breath? The Puranas describe the time between Kalpas as Brahma’s night—a pause, not an end.

“There is a mystery in the heart of time, and all we behold is but a shadow of its truth.” — Rabindranath Tagore

Now, stretch your mind further: Brahma’s full life consists of 100 divine years, each made of 360 days and nights, making a span of 311 trillion human years. At the end of this incomprehensible duration, everything—gods, worlds, even time—dissolves into the supreme reality, and a new Brahma is born. This image, of cosmic cycles spiraling out and returning, takes the anxiety out of endings and makes each conclusion a creative pause.

One aspect I find especially intriguing is how these grand scales of time shape Hindu ritual and philosophy. Daily worship, yearly festivals, and rites of passage all synchronize with this cosmic clock. The Puranas suggest that by aligning our lives with these cycles, we honor the principle that governs not just our world but the entire cosmos. There is comfort and meaning in knowing that the rhythm of your breathing, the change of seasons, and even your life stages echo far greater cycles above.

But the Puranas don’t stop at vast cycles—they engage with relativity in an almost modern sense. Stories within these texts toy with time travel: a sage enters a divine realm for a few days and returns to find centuries have passed on earth. It prompts us to ask: is time absolute, or is it perceived differently depending on your position in creation? Markandeya, for example, witnesses dissolution but survives, carried by divine grace through emptiness, experiencing time outside of its normal flow. His story implies that consciousness can, at least briefly, step outside the relentless march of time.

Ask yourself: How would you experience your life if you saw it as part of a sequence stretching back before creation and forward beyond destruction? Would setbacks feel different? Would triumph lose, or gain, meaning?

“We are not human beings having a spiritual experience. We are spiritual beings having a human experience.” — Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

There is a humility woven into this cosmology. When you recognize the brevity of human history compared to a Kalpa, the rise and fall of civilizations seem less like unique tragedies and more like seasons in an endless year. This perspective doesn’t breed apathy—it brings a kind of calm resilience, a willingness to accept change as not just inevitable, but essential. It encourages us to value rebirth and recognize that loss is not always final.

Another layer that fascinates me is the notion of ritual and ethical order synchronized with cosmic time. In the Puranic view, every act of worship, every sacrifice, and every festival is a microcosmic imitation of macrocosmic events. Our rituals aren’t just for us—they keep the cosmic wheels turning, as if human actions help sustain the rhythm of the universe. It’s a reminder that meaning isn’t isolated to the heavens; it’s created right here, in the turning of a prayer wheel, the lighting of a lamp, or the telling of a story.

“To realize the immensity of life, just watch the movement of time within and without.” — Sadhguru

At the heart of all this is a paradox. Time, in these stories, is both infinite and illusory. While the cycles spin endlessly, the divine—called Brahman—remains unchanged, beyond even the mightiest span of Kalpas or the deepest night of dissolution. For the Puranas, time exists for the sake of experience, learning, and renewal, but ultimate reality is timeless, untouched by the play of cycles.

This leads me to a crucial reflection: if the divine is beyond time, is liberation merely an escape from suffering, or an awakening to a state beyond cycles entirely? If so, even the grandest cosmology serves only as a passing stage—an elaborate drama through which souls journey, until they remember their true, timeless nature.

“Time is a created thing. To say ‘I don’t have time’ is to say ‘I don’t want to.’” — Lao Tzu

Maybe that’s why, despite its staggering timelines, the Puranic model of time is deeply practical. It asks us to reflect, act, and find our place in cycles vast and small. It assures us that every loss is seed for a hidden renewal, that no descent is without hope of ascent, and that the most fleeting moments belong to something infinite.

So, next time you notice seasons changing, or generations giving way to the next, remember that you are part of something much larger—a cycle that holds both your story and the story of the universe in its gentle, persistent turning. What will you do, knowing your moments echo among the ages?