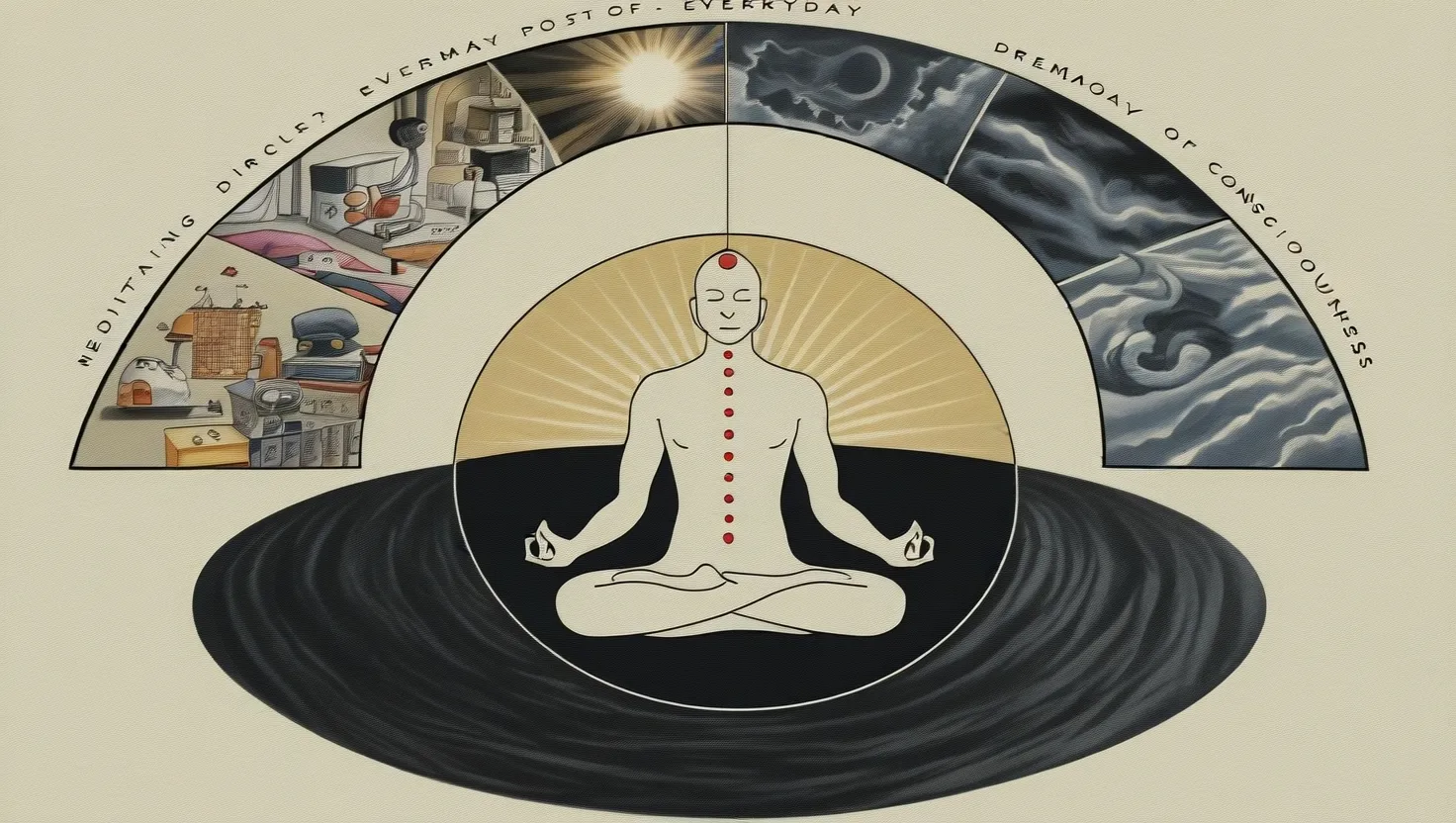

In the vast and intricate landscape of Vedantic psychology, the concept of Avasthas, or states of consciousness, stands as a pivotal yet often overlooked aspect. These states, which include the familiar waking, dreaming, and deep sleep, as well as the more enigmatic fourth state known as Turiya, offer a profound lens through which we can understand the nature of consciousness and reality.

Let’s begin with the waking state, or Jagrat. This is the realm where we are most familiar, where our consciousness is outward-facing, engaging with the world through our senses, mind, and intellect. Here, we experience the world in its gross form, interacting with physical objects and emotions. This state is characterized by the entity known as Visva, which consumes experiences through the thirteen instruments of the ten senses, the mind, intellect, and ego. Each of these instruments plays a crucial role in how we perceive and interact with our environment, recording physical events and emotions that will later influence our dreams and deeper states of consciousness.

As we transition into the dream state, or Svapna, our consciousness shifts inward. Here, the entity known as Taijasa takes over, and our mind is engrossed in the impressions and residues of our waking experiences. These impressions, or Samskaras, are the latent memories and emotions that surface in our dreams, creating a world that is both familiar and distorted. In this state, our emotional faculty replays recorded emotions, and our intellect is dormant, while the ego functions only through the memories stored in our mind. This subtle body, though partially functioning, reveals the power of our subconscious in shaping our perceptions.

Deep sleep, or Sushupti, is a state where our consciousness appears to be at its most subdued. Here, the entity known as Prajna dominates, and our mind is undistracted, free from the stimuli of the external world and the internal world of dreams. In this state, there are no emotions, no intellectual activity, and no sense of ego or identity. Yet, despite this apparent dormancy, there is an underlying awareness that persists. This state is often referred to as the seed state, where the subtle body is “as though” resolved into the causal body, awaiting the moment when it will sprout back into waking or dreaming consciousness.

Beyond these three states lies the enigmatic fourth state, Turiya. This is not just another level of consciousness but a transcendent state that underlies all the others. Turiya is described as the state of absolute silence and emptiness, where the distinctions between waking, dreaming, and deep sleep dissolve. Here, one experiences the infinite and non-dual nature of reality, unencumbered by the illusions of Maya. This state is not just a theoretical construct but a lived experience for those who have realized it, a state where the individual self merges with the universal consciousness.

The significance of these states extends far beyond mere psychological curiosity; they are gateways to profound self-knowledge and cosmic awareness. By examining these Avasthas, ancient seers and philosophers aimed to understand the very fabric of existence. The Mandukya Upanishad, for instance, delves deeply into these states, describing how each one reveals different aspects of our being and the cosmic truth. It emphasizes that Turiya is the substratum of all other states, the true state of experience where the infinite and non-dual are apprehended.

In practical terms, understanding these states can guide us in our spiritual practice. For meditation enthusiasts, recognizing the transitions between these states can help in achieving deeper levels of awareness. For instance, the practice of observing one’s thoughts and emotions during the waking state can prepare the ground for a more profound awareness in the dream and deep sleep states. Similarly, cultivating awareness during deep sleep can lead to a more stable and insightful waking consciousness.

The interconnections between these states are also noteworthy. The experiences and impressions gathered in the waking state influence our dreams, while the deep sleep state rejuvenates and prepares us for the next cycle of waking and dreaming. Turiya, being the underlying state, influences all other states, offering a glimpse of the ultimate reality that transcends the duality of the phenomenal world.

In Vedantic thought, the Atman, or the self, is seen as the witness to all these states. It is the immutable, ever-present consciousness that observes the changing landscapes of our experiences without being affected by them. This understanding is crucial for self-realization, as it helps in distinguishing between the transient ego and the eternal self. By recognizing that the self is the witness, we can begin to detach from the fleeting experiences of the waking, dreaming, and deep sleep states and move towards a more profound understanding of our true nature.

The exploration of Avasthas also highlights the limitations of Western philosophical approaches, which often focus solely on the waking state. By considering all three states—and the fourth state of Turiya—Vedantic psychology offers a more comprehensive and holistic view of human consciousness. This inclusive approach acknowledges that each state has its own reality and significance, contributing to a richer understanding of human existence.

In conclusion, the states of consciousness in Vedantic psychology are not just abstract concepts but living, breathing aspects of our daily and spiritual lives. By delving into the nuances of Jagrat, Svapna, Sushupti, and Turiya, we open ourselves to a deeper understanding of consciousness, reality, and our place within the cosmos. This journey into the heart of Avasthas promises not only to enrich our spiritual practice but also to illuminate the path to self-realization and cosmic awareness. As we navigate these different levels of awareness, we may find that the distinctions between the self and the universe begin to blur, revealing a unified, timeless truth that underlies all existence.